I feel compelled to write about the Baltimore Fire, not just because it was awful and terrible and burned most of what is now Baltimore’s business district to the ground, but because my family was directly involved.

On Sunday, February 7, 1904, an explosion at the John E. Hurst & Company building. broke windows and sent flames onto the roofs and through the windows of neighboring buildings. Within minutes, they too were burning, threatening even more real estate. The Hurst building was located between Hopkins Place and Liberty Street on what is now Redwood Street (was German Street). The location is now the southeast corner of the Baltimore Civic Center/Royal Farms Arena. It was almost 11:00 in the morning. My great-grandfather, Christopher Miller and his family and his extended family (in-laws), the DuValls, were no doubt in church at the newly constructed Boundary United Brethren Evangelical Church (the old wooden church, not the stone church that sits there now), a mere block from their home at 505 Franklin Terrace when the explosion occurred. He had no idea that the business he managed was on the verge of burning to the ground.

WISE BROTHERS SHIRT FACTORY & MY GREAT-GRANDFATHER

Wise Brother’s was a shirt factory located at 126-132 West Fayette Street (corner of West Fayette and Little Sharp Street – just a block west of Charles Street). On the northwestern edge of the fire, the large 6 story factory building contained (per an article in the November 1903 Sewing Machine Times) 3000 sewing machines, lots of fabric and tons of paper and it sat a mere two or three blocks from the Hurst Building. A huge addition had been completed a mere 5 years previous, adding 12,000 square feet of space to the building (so as to add 1500 sewing machines), and it had added its very own electric light plant. They employed mostly men, not because of sexism, but apparently because they couldn’t find enough good female seamstresses. They finally gave up in 1903, and placed an ad in the local paper stating that they would employ men and boys over 15 if they could sew. They were also the very first factory business in Baltimore to employ African-American women – starting at about 1900. By 1912 there were close to 300 African-American women working at the factory, making the same wage as everyone else.

Born to German parents, Christopher was one of ten children, and three of his brothers, a sister and a nephew, all worked at the factory. Christopher began as a bookkeeper and became the general manager, his brother Edward was also a manager and was eventually given a satellite factory in Harrisonburg, Virginia, to manage in 1917. Christopher’s older brother George was a desk manager, baby brother Harrison was a shirt cutter, sister Annie was a saleswoman in addition to being a seamstress. George’s son Albert became a bookkeeper for the company and their father Frederick worked part-time as a watchman at the factory after he retired as a photographer. Christopher married in 1897 to Ella Maude DuVall, an 8th generation descendant of Mareen DuVall, the French Hugenot immigrant to Anne Arundel County. My grandmother Helen was born in 1898 and was just 5-6 years old at the time of the fire, and she told me that she remembered her father and his brothers getting up from Sunday dinner, rushing out of the house, and getting on the streetcar and going downtown. She knew that something terrible had happened but didn’t understand it all until a bit later that day. Her father was 32. George was 34; Eddie was 30. Harrison was just 16.

l) My great-grandfather – Christopher Miller – taken about the time of the fire. He was born in 1872 and died in 1944. He was named after his mother’s brother, Christopher Schaefer, who was named after his mother’s brother Christoph Diering. My father was also Christopher, named after him. r) the interior of Wise Brothers – laundry area

The boys that fought to keep Wise Brothers from burning – back row Harrison, Eddie, Chris and George – the front row is sisters Cora, Clara, Rose and Annie. Photo taken in 1938.

Franklin Terrace is now East 41st Street and sits between Greenmount Avenue and Old York Road in the PennLucy section of the city near Govans. The old house is still there. The #8 streetcar ran up and down Greenmount Avenue from Towson into the city. I’ve no idea how long it took my great-grandfather and his brothers to get where they were going – a half-hour? 45 minutes? They’d had to have changed street cars a few times to get west of the harbor and then possibly walked. It was Sunday – were all the lines open? I’ve no clue. I assume too that the factory was closed. I do know that by 4 p.m. Sunday, the electric streetcars had failed.

l) Taken from a 1905 map of Baltimore – the area in orange is the fire zone

r) A map of the burn zone (click to view the map full size)

ENGINE 15, THE HORSES & THE START OF THE FIRE

In the time it took my great-grandfather to get on the streetcar, the Salvage Corps, Fifth District Engineer Levin Burkhardt, Engine 15 and Truck 2 had responded to the automatic alarm, turned in by fire patrolman Archibald McAllister, at the Hurst Building. It was 10:50 am. Engine 15’s captain, John Kahl, initially saw only smoke coming from the roof of the building. He checked the alarm box (#447 located at the corner), which told him that the fire was in the basement, so he ordered his men in. Smoke filled the first floor telling him that this was more than just a small fire. He sent men in to hose down the elevator shaft and sent men towards the basement. Because they had broken in using a crowbar (there was no watchman in place to let anyone in), and had given what had probably been a long smoldering fire fresh oxygen, and could see flames on the ceiling and smoke heading toward the elevator shaft, what most likely occurred was a backdraft. It is now assumed that a lit cigarette or cigar dropped on the sidewalk, fell through a broken “deadeye” (a 2 inch circle of glass put there to let sunlight into a basement) in the sidewalk tile and landed in the building’s basement and smoldered for what could have been hours. The ensuing explosion literally blew the roof off the building and blew out the windows , knocking Captain Kahl and 4 other firemen (Guy Ellis, John Flynn, Harry Showacre and Jacob Kirkwood) back into the street. It was a 6 story dry goods company, almost everything inside was flammable. The other firemen inside were able to escape without injury, however, the lead horse for Engine 15 was severely burned. The enormous, 1 ton, white/dapple grey percheron, named Goliath, the head of the three horse team, was pulling the Hale Water Tower into position on Liberty Street when the building exploded. The other two percherons, named Decoration and Electioneer, had already been unhitched and were standing nearby, leaving just Goliath at the curb, still hitched to the 65 foot, 5 ton tower. Brick and stone fell onto the engine sitting on German Street, crushing it and flames went everywhere, shooting out the front door of the business, searing the horses now standing on Liberty Street. All three animals were injured, along with the teams driver, Eugene Short. Goliath’s burns were the worst, because of his position at the curb (the lead horse always had the curb position to keep the engines or whatever they were hauling away from the curb and out of the gutter), but despite his horrible injuries, he quickly veered the tower away from the falling debris, saving the 4-5 firemen on the tower’s wagon, the driver, and pushing Decoration and Electioneer out of the way at the same time, thereby keeping humans, horses and tower all from being crushed. Now the only horse hitched to the tower, he strained to free the trapped fire apparatus and steered it through an obstacle course of falling, fiery, wood, brick and rubble. Unable to move forward, driver and horse then worked against time to attempt a u-turn in the tight confines of Liberty Street, in order to save the tower. Short’s face, arms and hands were badly burned in the effort to get the already injured Goliath and the water tower away from the toppling building. As soon as horse, man and tower had cleared the corner at Liberty Street, what was left of the building finally collapsed. Decoration and Electioneer stayed with the fire crew as they moved south and east toward Pratt Street. Goliath was rushed to the Fire Department’s vet on West Lafayette Street. Engine 15 battled along the water front until midnight and were finally ordered to approach the fire from the east, so again, they re-hitched the horses, and had to go north up Howard Street and east across Centre Street and back down East Falls Avenue. They wouldn’t return to their Lombard Street home until Tuesday after stamping down small fires that had flared back up. They had been out the longest, for 55 hours – still in their dress uniforms. Sunday they had been turned out for an inspection that never happened.

Above – pics of the Hurst Building – where it all started

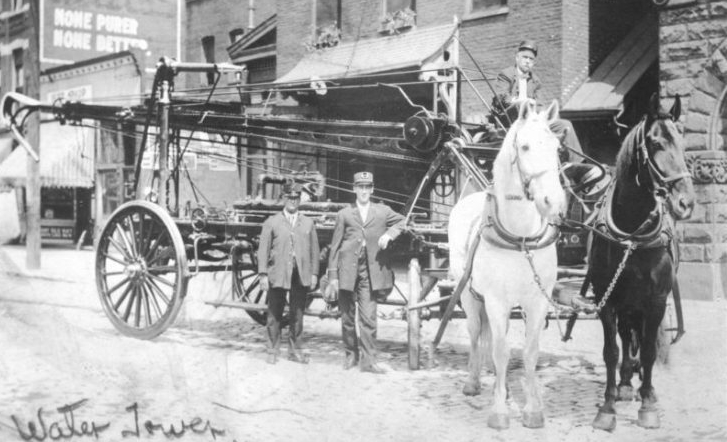

A water tower similar the one the 3 horse team was pulling. They weighed 5 tons and would later take a semi-engine to haul.

11:00 AM SUNDAY

Within minutes of the explosion at the Hurst Building, four other buildings had caught fire, because of debris thrown into the air. A nightwatchman in the National Exchange Bank across the street, on duty during the day because it was Sunday, was blown out the window of the Bank. His clothes caught fire and he got up and headed toward Baltimore Street where he finally collapsed. He woke up in the hospital. Next door to Hurst’s was a hardware store with barrels of coal oil and gasoline on the sidewalk outside. The flames finally reached that as well, and there were more explosions.

By 11:10 am the entire Baltimore City Fire Department had been called to the scene, a total of 24 engines and 8 hook and ladder trucks. By noon, Baltimore’s Fire Chief, George Horton realized that the fire was slowly spiraling out of control so he sent a telegram to Washington D.C. requesting help – it read “Desperate fire here. Must have help at once.” The wind was heavy and was blowing from the southwest to the northeast, taking the fire in the direction of City Hall and the courthouse. By 1:30 in the afternoon, fire companies from D.C had arrived on the train but quickly determined that their hose couplings didn’t fit Baltimore’s hydrants. They were quickly jerry-rigged to fit, but weren’t as efficient. The temperature was around 20 degrees and the wind was a blowing at 25-30 mph.

5:00 PM SUNDAY

At 5 pm it was decided to start building a fire-break by using dynamite. This just made the fire spread, rather than helping to contain it, and several buildings they attempted to blow up stubbornly remained standing. Others remained standing because their owners, like Irishman, Thomas “Pinky” O’Neill, refused to let them be blown up. He literally told the fire department that they would have to blow him up with the store and then ordered his employees to flood the roof of O’Neill’s Department Store using the water tank, plug up the downspouts and then ran off to the Carmelite Convent on Biddle Street where he begged the nuns (including his sister) to pray to the Blessed Mother for his store. Whether divine intervention, or just a fickle shift in the wind, O’Neil’s Department Store at the southwest corner of Charles and Lexington did not burn. Debris from other dynamited structures blew across the old narrow streets, igniting other buildings. By 6 pm the wind had shifted and was now blowing due east, sending the fire in that direction, rather than north, which saved the old courthouse and City Hall, by a mere block. And by block, I mean the other side of the street burned. Fire crews from Philadelphia and Delaware had arrived by this time too, but ran into the same issues as the D.C fires crews with the hose couplings. Telegraph offices began to fall, so to stay in touch with the outside world, telegraph operators moved into the upper floors of the brand new Belvedere Hotel, some 11 blocks north. The B&O Roundhouse was just outside the burn zone and because the streetcars were no longer running, volunteers used wheelbarrows to transport coal from the railyard to the the fire engines that desperately needed it for steam to keep their pumpers working. South Baltimore’s Jewish population kept firemen in coffee and tea and gave them warm a place to actually sit down and rest, especially those from out of town. Businesses on Camden Street donated ear muffs, mittens, wool socks and caps – all to the firemen and police officers.

MIDNIGHT MONDAY

By midnight, the Maryland National Guard had 2000 soldiers and sailors from the 4th and 5th Maryland, and the Naval Brigade, in place to deal with crowds of looters spectators in the fire district and sightseers that were starting to arrive on boats. A company of army regulars from Fort McHenry was sent into the city as well to aid the police. The regulars were withdrawn on the 8th but the National Guard would stay in place on guard duty in the burnt areas until February 23. Crowds had been interfering with the firefighters and police had to slowly move then back one block at a time as the fire crept forward. As Monday morning dawned, with the fire still crawling eastward towards the Jones Falls, the wind shifted yet again and the fire moved south east along Pratt Street from Light Street. More fire companies arrived from York, Chester, Altoona and Harrisburg and by 6 am, firefighters from Philadelphia attempted to stand their ground on the Pratt Street docks in a brave effort to protect the wharves. In the face of 25 mph winds, by 8 am, the wharves were lost, but Federal Hill and South Baltimore had been protected thanks to them and Baltimore’s fireboat, the Cataract. With the fire still raging east bound, the only hope of saving Jonestown and the rest of east Baltimore was the Jones Falls itself. People living in Little Italy had gone to bed fully dressed, with someone standing watch, while others streamed into St. Leo’s, asking for the same intersession that Thomas O’Neil had. East Baltimore’s Jewish community was also at risk, along with the Lloyd Street Synogague – and it was very quickly determined that if the fire jumped the Jones Falls and set Jonestown alight, due to the crowded nature of the area, no attempt would be made to extinguish the blaze. This meant that if the wind kept up, and Jonestown burned, the fire could then reach Fells Point and then Canton and Highlandtown.

National Guardsmen on duty during and after the fire. – Library of Congress photos.

11:00 AM MONDAY

A decision was finally made to establish a fire department stand along the then 75 foot wide Jones Falls. At 11:00 am, nine engines companies from New York City, along with two more engine companies from Wilmington, Delaware, and Engine 15, were placed along it’s east bank and along 5 bridges spanning it. A total of 37 steam engines took water from the Jones Falls from Baltimore Street south and literally created a wall of water to halt the advancing fire. By 3 pm the fire was contained and by 5 pm it was completely under control, although it would be weeks before everything was extinguished. Most schools in the area, including Baltimore City College (then at Howard and Center Streets) closed for about 2 weeks.

The Cataract, Baltimore’s fireboat, shot from Federal Hill, fighting the blaze on the Pratt Street docks from the harbor; the Jones Falls, shot from the east side after the fire, The Cataract moored at her dock

1231 firemen, professional and volunteer, helped bring the inferno under control along with many, many horse teams who pulled the water towers, the ladder trucks and the pumpers.

All in all, an 86 block area burned (180 acres) in just 30-31 hours. Over 1500 buildings were leveled and 1000 were left with severe damage. 2500 businesses were gone. 22 banks were destroyed, although all of the banks vaults held – 11 trust companies, the chamber of commerce, the stock exchange, all but one newspaper office, (The Baltimore Herald, The Baltimore Sun, The Baltimore American and the The Baltimore Evening News were all destroyed) the railroad office, a church, hotel, theaters and business buildings of every kind, new and historic were decimated. The 1851 home of the Maryland Institute College of Art burned to the ground. The Central Post Office also burned and only the quick thinking of letter carrier Thomas Lurz saved tons of mail from being destroyed. He corralled a group of men who loaded bags of it onto wagons and took it north and finally left it in the care of the National Guard. Max Levinson, the Russian immigrant owner of Baltimore’s premier Jewish Funeral Home lost his entire business in the fire.

The damage was estimated at close to $100,000,000.00 (3.84 billion dollars today). 35,000 people were at least temporarily out of work. By some miracle, it is recorded that no civilian lives were lost and no homes were lost – the destruction was just in the business district, which was blissfully closed because it was Sunday. Over 50 firemen were injured and others involved would later experience complications from smoke inhalation, pneumonia, and other lung diseases. Five deaths were indirectly blamed on the fire. Two members of the National Guard, Private John Undutch and Second Lieutenant John V. Richardson both became sick and died of pneumonia, most likely from standing outside in the bitter February cold. Fireman Mark Kelly and Fire Lieutenant John A. McKnew also died of pneumonia due to exposure as well. Martin Mullin, the proprietor of Mullin’s Hotel (West Baltimore and North Liberty Streets, above Hopkins Place), a block north from Hurst Building, also later died. A sixth, was an unidentified African-American man found burned and floating in the harbor at Pier 2 by the Naval Reserve. He was never identified, nor was anyone meeting his description reported as missing. Baltimore’s youngest Mayor at the time, Robert Milligan McLane, died in May of 1904 from a gunshot wound to the head. His death was ruled a suicide as he was dealing with the stress of the rebuilding the city. He had refused all assistance from other cities and had returned donations. It was also reported that a local merchant died from a heart attack while attempting to quickly remove goods from his business.

It was deemed to be the nations third worst fire, after the Chicago Fire and the San Francisco Fire following the earthquake. Federal hydrant standards were to be put in place just two years later because of the hose coupler issues that the out-of-state fire companies had with our Baltimore hydrants. Baltimore very quickly rebuilt, but the old colonial city was forever changed. Narrow streets were widened, electrical was placed underground and a plan was put in place to separate the storm drains and the sewage drains and to treat industrial and human waste before returning it to the bay.

THE NORTHWEST CORNER OF THE FIRE

I don’t know precisely when on Sunday my great-grandfather arrived at the business he loved and managed, but according to my grandmother, he and his brother’s and several dozen employees formed a bucket brigade and poured water on the Wise Brothers building most of Sunday to keep it from burning. It was one of 10 buildings that didn’t burn. It sat, quite literally, at the northwest corner of the fire. Anything burning that hit the roof was quickly dowsed with water and/or tossed over the edge. Days after the fire, photos were taken from its roof of the devastation. He had saved the building, the business, and saved not only his own job, but the jobs of thousands of people employed by the company. Lawyers and clerks had done the same at the courthouse, congregants had done it at the First Baptist Church over on Lombard Street – and everyone had emerged covered in soot, looking like strangely dressed coalminers. My grandmother told me that afterwards, her mother deposited her father’s clothes in the trash heap. They wouldn’t come clean of the smell or the filth.

My grandmother also said that she stood on the back porch of her home Sunday night with her mother and looked south and she told me that the sky glowed an eerie, undulating orange-red. You could see smoke, not flames, but it was very evident that the city was burning. She said you could smell it too – as far north as they were. She was just six at the time and her sister was two, but she was old enough to know that her father had disappeared with her uncles into something very dangerous and she and her mother had no clue as to whether any of them were safe or not. It would be 4 days before she saw him again. In a world without cellphones, the wait must have been agonizing. She later said he stayed and slept at the factory, mostly because he couldn’t get home because the streetcars weren’t running and secondly to protect the place from looters that were all over the place. Even with the National Guard in place along with Baltimore’s Police, as the manager, he apparently wasn’t taking any chances.

DOWNTOWN TODAY

Another side note – if you drive downtown at all, you’ll notice the effects of the fire even today. The streets in the business district and around the harbor are wide, but as you move north to leave the city, as thousands do every day, you leave the business district and subsequently the old burn zone. Streets narrow and traffic bottlenecks above Fayette Street. Every. Day. It is particularly noticeable on Charles Street and Light Street. Fireproofing standards were put in place and marble and steel became the building materials of choice rather than wood.

FIREFIGHTING UNITS THAT AIDED BALTIMORE

- Annapolis (20 miles by Annapolis & Baltimore Railroad)

- Independent Engine Company Number 2

- Water Witch Hook and Ladder Company

- Hamilton (6 miles by road)

- Havre De Grace (36 miles via railroad)

- Highlandtown (2 miles by road)

- Engine Company Number 2

- Relay (9 miles by B&O Railroad)

- Fire Company Number 1 (hand pumper)

- Roland Park (4 miles by road)

- Engine Company Number 1

- Sparrows Point (10 miles by tolley)

- Volunteer Fire Company Number 1

- St. Denis (9 miles via B&O Railroad)

- Number 2 Reel Company

- Westminster (36 miles by ROAD)

- Westport (3 miles by road)

- Washington D.C. (45 miles via B&O Railroad) – Co. 3 & 6 arrived 1 hour 49 minutes after the first alarms. They must have really hauled ass.

- Engine Company Number 2

- Engine Company Number 3

- Engine Company Number 6

- Engine Company Number 7

- Engine Company Number 8

- Altoona, PA (217 miles via PA Railroad)

- Altoona Engine Company

- Chester, PA (84 miles via B&O Railroad)

- Henley Engine Company Number 1

- Felton Engine Company Number 3

- Columbia, PA (66 miles via railroad)

- Columbia Steam Engine & Hose Company Number 1

- Harrisburg, PA (85 miles via Northern Central Railroad)

- Hope Engine Company

- Hanover, PA (56 miles via railroad)

- Hanover Steam Fire Engine Company Number 1

- Philadelphia, PA (98 miles via PA Railroad)

- Engine Company Number 11

- Engine Company Number 16

- Engine Company Number 18

- Engine Company Number 20

- Engine Company Number 21

- Engine Company Number 23

- Engine Company Number 27

- Engine Company Number 43

- Phoenixville, PA (101 miles via PA Railroad)

- Phoenixville Engine Company Number 1

- York, PA (58 miles via Northern Central Railroad)

- Laurel Engine Company

- Vigilant Engine Company

- Wilmington, DE (72 miles via B&O railroad)

- Frame Hose Company Number 6

- Friendship Engine Company Number 1

- Weccacoe Engine Company Number 8

- Reliance Engine Company Number 2

- New York City (1st Wave) – (187 miles via PA Railroad and NJ Central Railroad)

- Engine Company 5 – 340 E. 14th Street

- Engine Company 7 – Beekman Street

- Engine Company 12 – 261 William Street

- Engine Company 13 – 99 Wooster Street

- Engine Company 16 – 223 E. 25th Street

- Engine Company 27 – 173 Franklin Street

- Engine Company 31 – White & Elm Street

- New York City (2nd Wave)

- Engine Company 26 – 37th Street Between 7th and 8th Ave (returned to NY with a dog named “Baltimore”)

- Engine Company 33 – 42-44 Great Jones Street

- Hook and Ladder 5 – 96 Charles Street

- Atlantic City, NJ (150 miles via B&O Railroad)

- United States Company Number 1 (volunteers)

- Neptune Hose Company Number 1 (volunteers)

- Trenton, NJ (135 miles via PA Railroad)

- Engine Company Number 1

- Alexandria, VA (51 miles via railroad)

1400 Firefighters, including ones that fought the fire, were honored in a parade on September 13 1906, celebrating Baltimore’s rebirth from the ashes at the end of “Jubilee Week”. All of Baltimore’s department as well as firemen from above departments, marched in the parade. Among them, covered in flowers, proudly wearing his scars, was Goliath, who it is said, pranced and danced at the reviewing stand and appeared to wholly understand the crowds adulation.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Just to prove that I actually do use sources.

Information thanks to:

Personal knowledge of Helen Margaret Miller DeVier (1898-1985) as told to Suzanne C. DeVier

Maryland Historical Society

The Fire Museum Of Maryland

“The Great Baltimore Fire” by Peter E. Petersen, pub. 2005

“A Trip Through Wise Bros. Establishment” November 23, 1912, The Baltimore Afro-American

“First Man On The Scene” by John Kahl, BCFD Retired, February 7, 1954, The Baltimore Sun

“Recalling The Great Fire” Feb 6, 1984, The Baltimore Sun

“Great Baltimore Fire” – Wikipedia

Sun archives: The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-great-baltimore-fire-begins

“Lost In The Great Fire” by Carl Schoettler, February 5, 2004, The Baltimore Sun

The 1904 Fire and the Baltimore Standard, by Bruce Goldfarb, Welcome to Baltimore Hon!

“Cheers And Praise For Firemen On Parade” September 14, 1906, The Baltimore Sun

“Your Maryland” by Ric Cotton, pub. 2017.

“Goliath’s Last Alarm” June 131, 1913, The Baltimore Sun

“Two More Horse Heroes” June 15, 1913, The Baltimore Sun

“Horse: King For A Day” May 31, 1914, The Baltimore Sun

“Goliath: Hero of the Great Baltimore Fire” by Claudia Friddell, pub. 2010.

“Goliath” by Ric Cotton, WYPR, February 2, 2016

The Ordinances of the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore #27 – Resolution to provide for the retention by the city of the horse “Goliath” in recognition of his great services at the Great Fire February 7/8 1904.

Wonderfully informative and well-researched article. I particularly appreciate the family story, the data about Wise Bros., and the “Order of Battle” for the mutual aid companies that rushed to the city’s rescue. Although I have been doing some research of my own as a supplement to my genealogical studies, nowhere else have I found particulars of the city’s six, human casualties. There must have been many other firemen and volunteers who, years later, suffered or died from lung ailments related to their inhalation of the soot amalgamated from all the incinerated paints, varnishes, chemicals, drugs, etc. (cf. the long-term pulmonary casualties from the burning of the World Trade Center towers in New York, 2011). My mother’s forebears, Keyser, Dier, Dopman, Whitman, Barton, and Wheeler (the latter two veterans of the Army of the Potomac) were all living in the eastern part of the city during the fire and likely experienced at least some of the same tension as your Great-grandmother that night of Sunday – Monday. I have wondered whether any of them might have gone to bed fully dressed, with packed bags, leaving one awake to keep watch. Thank you again.

Thank you so much for you kind response. My family has been in B-more since the War of 1812. I love this city and though blogging about it and researching things that I sort of know, but want to know more about would be a way to show my love for the city.

Fire Captain John Kahl is my great-great grandfather. I am trying to find the article from the Baltimore Sun “First Man on the Scene” about him, and send it to my son who is a firefighter. Any assistance would be much appreciated. Thank You

BCPL.info is the Website for the Baltimore County Library. Get a login – you don’t need a library card. Go to the research database and then to ProQuest which is the Baltimore Sun archives. You can search it that way or by Kahl’s name. That how I found it.

Hello: It’s the end of 2021 and I don’t know if you are still receiving letters. Working through Ancestry.com, I just learned that my (Great) Uncle Charlie (Charles Albert Hardy) also worked at Wise Bros on Fayette Street. I knew as a boy that he was somehow involved with the clothing industry because my Mother always spoke about ‘Uncle Charlie’ dressing so well. (Now I know why). He was my Grandmother’s brother. Her name was Carrie Hardy Murphy and I believe that as a young woman in the early 1900s she also worked at Wise Bros. If not Wise Bros then she worked at another company located in Baltimore’s garment district. Happy New Year to you for 2022. Charles J. Murphy, Howard County.

I am! Good to meet you. I don’t of too many folks who even know or remember Wise Brothers. My grandmother always spoke of it but with the older generations being gone I fear so much of the city and it’s history will become lost to time. I do know that my great-granddad was able to gather a few employees on his way to fight the fire – perhaps your Uncle Charlie was one of them. Would be cool to know he helped.